Introduction

It sets the stage for the reader, and it should capture the reader’s attention and generate an interest in continuing to read the research article.

(Turner, 2018, p. 103)

Introduction

An Introduction section should provide the following characteristics:

- development of the problem under investigation,

- including its historical antecedents, and

- statement of the purpose of the investigation.

(APA, 2010, p. 10)

Photo by Etienne Girardet on Unsplash

The Introduction Section

Many scholars use the visual image of an inverted pyramid or a funnel to describe how the compelling problem can be effectively communicated. Typically the top portion of the funnel provides an articulation of the phenomenon of interest and why it is important, and an executive synthesis of the relevant literature helps to illustrate what is currently known about the phenomenon. Ultimately a narrowing of the funnel begins to occur that then considers what is not known about the phenomenon relative to the specific problem being given attention. Then the actual gap in the empirical literature is highlighted and reflects the narrowing of the funnel. At the bottom base of the funnel, it should become very clear that an important problem requires further research because the problem associated with the phenomenon and the lack of empirical attention that has been given to it demands more research. This typically results in the articulation of a statement on the purpose of the study that clarifies the intentionality of the research. Journal manuscripts typically embed this material in an initial ‘Introduction’ section that concludes with a concisely stated purpose statement associated with the study.

(Ellinger & Yang, 2011, pp. 116-117)

Points to Consider

The following points of consideration were recommended for an Introduction section by Bryman (2016):

- You should explain what you are writing about and why it is important. Saying simply that it interests you because of a long-standing personal interest is not enough.

- You might indicate in general terms the theoretical approach or perspective you will be using and why.

- You should also at this point outline your research questions.

- The opening sentence or sentences are often the most diccisult of all…. It is much better to give readers a quick and clear indication of what is going to be presented to them and where it is going. (p. 664)

APA Manual

The APA manual (2010) identified the following questions that should be answered in any Introduction:

- Why is this problem important?

- How does the study relate to previous work in the area? If other aspcets of this study have been reported previously, how does this report differ from the earlier report?

- What are the primary and secondary hypotheses (or research questions) and objectives of the study, and what, if any, are the links to theory?

- How do the hypotheses and research design relate to one another?

- What are the theoretical and practical implications of the study?

(p. 27)

Questions to Ask about your research project and problem statement.

Ask often througout entire project.

- Ask how the topic fits into a larger context (historical, social, cultural, geographic, functional, economic, and so on).

- How does your topic fit into a lartger story?

- How is your topic a functioning part of a larger system?

- Ask questions about the nature of the thing itself, as an independent entity.

- How has your topic changed through time? Why? What is its future?

- How do the parts of your topic fit together as a system?

- How many different categories of your topic are there?

- Turn positive questions into negative ones.

- Ask speculative questions.

- Ask What if? questions. How would things be different if your topic never existed, disappeared, or were put into a new context?

- Ask questions that reflect disagreements with a source: If a source makes a claim you think is weakly supported or even wrong, make that disagreement a question.

- Ask questions that build on agreement: If a source offers a claim you think is persuasive, ask questions that extend its reach.

- Ask questions analogous to those that others have asked about similar topics.

- Look for questions that other researchers pose but don’t answer.

- Find a Web discussion list on your topic, the ‘lurk’.

(Turabin, 2007, pp. 15-17)

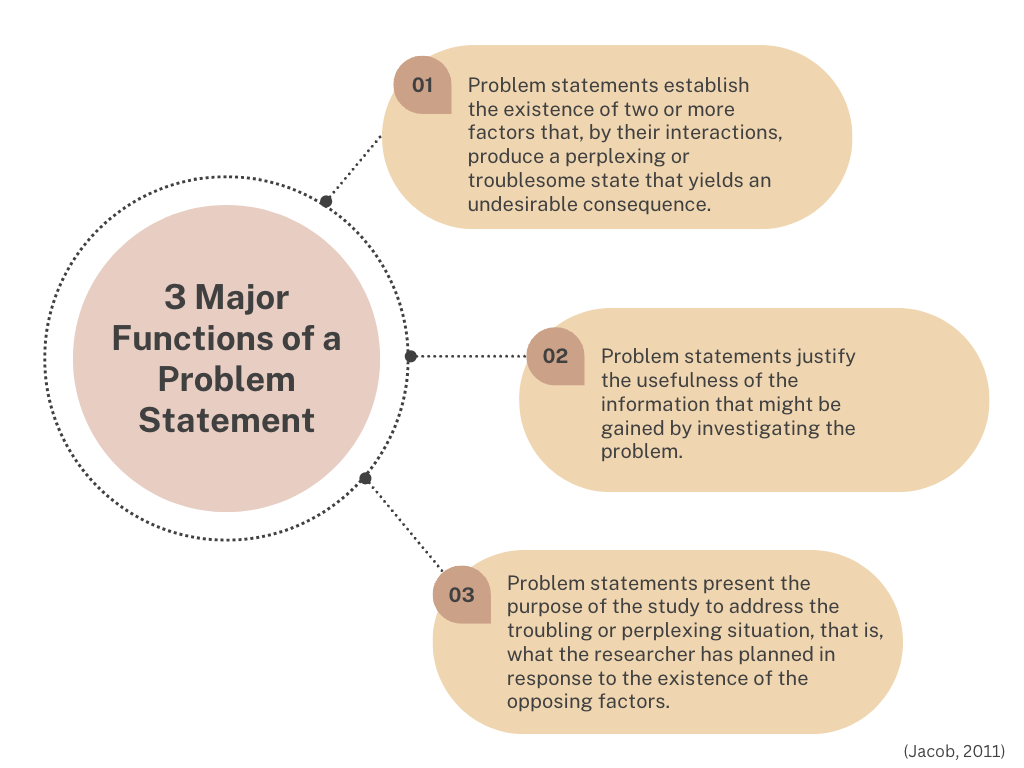

Three Major Functions of a Problem Statement

The information that forms the problem statement must be first induced from the literature, framed around certain theoretical understandings, and articulated in a way that clearly represents the interests of the researcher.

Process for Developing a Problem Statement

- Identify a topic of scholarly interest.

- Develop expertise on the topic and its supporting bodies of knowledge through the literature and experience.

- Induce potential research problems through a process of continually analyzing and synthesizing the information.

- Confirm the truth of a research problem through the literature, discussion, and peer review.

- Construct a formal problems statement to ensure the logic of the research problem and communicate the problem to others.

(Jacob, 2011)

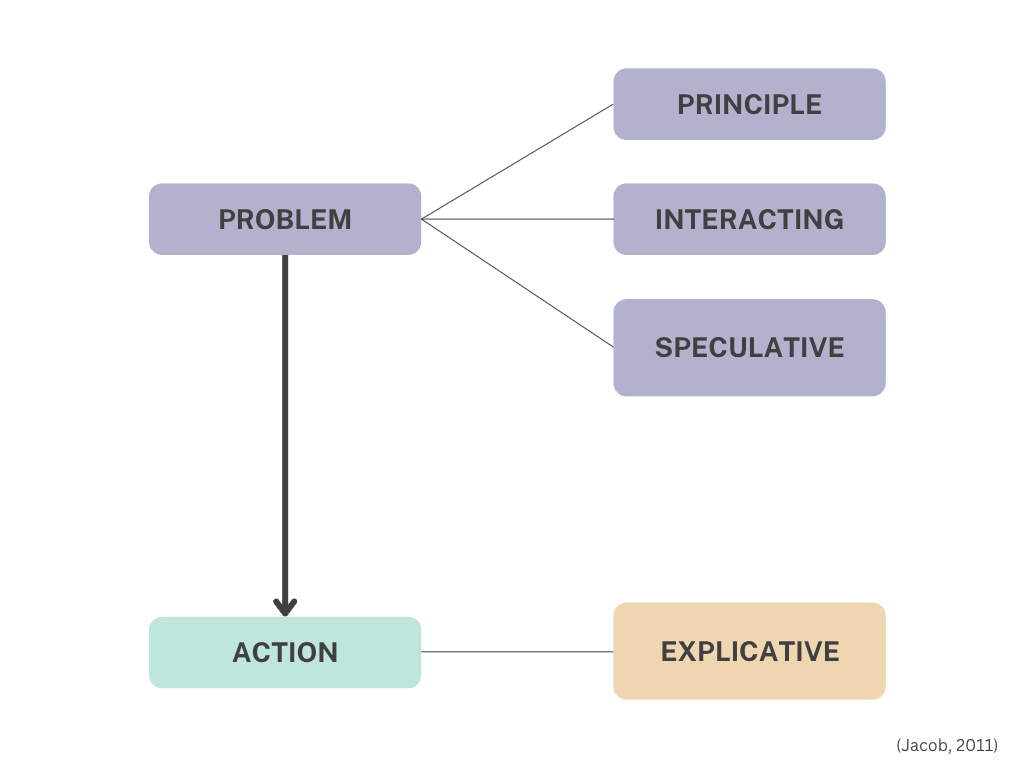

Constructing Problem Statements

Problem statements typically have four main components that contribute to the communication of the study’s problem that is being researched.

These four components include:

- Principle Proposition/Statement

- Interacting Propostiion/Statement

- Speculative Proposition/Statement

- Explicative Statement

Problem statements are certainly not built from personal opinions of the individual researcerh or conclusions made from spurious sources of information that may have an inherent predisposition or perjudice about a topic. In this sense, research problem statements can be construucted to appear to be logically valid, but they may not actually be true in the manner that truth is defined here. Viewing problem statements in this way highlights the need to differentiate the quality of the scholarly sources in a field, including conference proceedings, journals, and professional texts. In general, the most ‘truthful’ scholarly scources are those that have undergone the most rigorous review processes.

(Jacob, 2011, p. 134)