Theory

“With human observers in the center of the stage, the world is viewed from the human vantage point…. In short, theories serve human purposes; their creation is motivated and their logic organized by the skills and limitations of human capabilities.”

(Durbin, 1978, p. 7)

Theory

The idea of research is to present unbiased results that provide scientific laws, free of human will, aiding in one’s understanding of phenomena (Reed, 2006). Removing the human will, as identified by Reed, helps to benefit decisions on policy, politics, as well as benefiting the outcome of new medical advances in procedures and medicines, etc…

By organizing research, the foundation of the research is organized through theory, providing direction for the researcher to follow rather than interjecting their personal bias. Theory, in this sense, helps to provide researchers with a tool to conduct ethical and unbiased research.

Theory is about the connections among phenomena, a story about why acts, events, structure, and thoughts occur. Theory emphasizes the nature of causal relationships, identifying what comes first as well as the timing of such events.

(Sutton & Staw, 1995, p. 378)

Definitions:

A conceptual framework that identifies the connections, or lack of connections, between concepts/constructs to describe a phenomenon that furthers the academic knowledge base and supports researchers and practitioners in the field in which the phenomenon takes place.

(Turner et al., 2018, p. 38)

The mental image or conceptual framework that is brought to bear on the research problems.

(Van de Ven, 2007, p. 19)

A system of coherent, disciplined and rigorous knowledge and explanation.

(Lynham, 2002, p. 229)

Theory, Science, and Philosophy

As philosophy looks broadly at answering questions relating to the universe and how we fit in such a grand stage, questions that are often addressed by philosophers can seem “far removed from practical concerns” (Godfrey-Smith, 2003, p. 1). This pragmatic component (its practicality) is what differentiates philosophy from science. Science is narrower in focus, and compared to philosophy, addresses more immediate and local needs. This doesn’t discount the value of philosophy; it only identifies that science must provide practical solutions to today’s problems before being considered worthwhile. In science, there is an expectation of producing results, of solving problems, and of improving our understanding and knowledge.

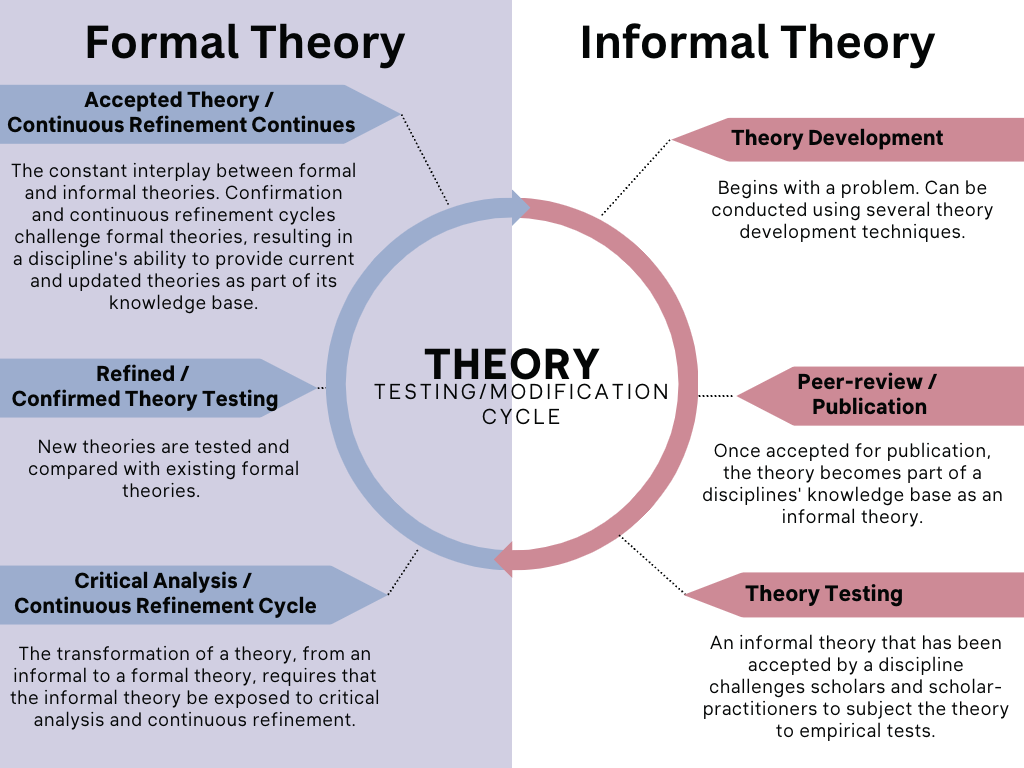

As a process to test our understanding of the world around us, scientific research helps to solidify our understanding as well as adjust our knowledge when it is incorrect (Jaccard, 2010). One key determinant to this knowledge creation through scientific research is the process of developing and testing theories. For the scientific process requires both, the development of a theory and the testing of that particular theory, in order to determine if the theory is accepted as an adequate explanation to a phenomenon, above and beyond that of previously tested theories. As stated by Jaccard (2010), “scientific theories do not constitute science until they are (or at least can be) subjected to empirical testing” (p. 27). This point is highlighted by Popper’s statement: “a theory is scientific to the degree to which it is testable” (Popper, 1985, p. 123).

A theory published through peer-reviewed processes begin the first stage of a theory becoming accepted as a plausible explanation of a phenomenon. The next step is to test this plausible explanation. By testing a theory, one can either confirm or disconfirm the theory as a valid explanation of the phenomenon. This confirmation process, method of verification, or testability (Godfrey-Smith, 2003) provides evidence for the possibility of a theory showing “observational evidence that would count for or against the proposition [theory] in question” (p. 27). If empirical tests show that the theory does not provide an acceptable explanation, researchers modify the theory, followed by further testing. This cyclical process is referred to the research cycle in its most basic form. The goal of this research cycle, according to Popper, is to produce “theories of even richer content, of higher degrees of universality, and of higher degrees of precision” (Popper, 1985, p. 164).

What Theory Is Not:

Sutton and Staw (1995) presented five ‘Wrong Way’ signs for authors on what theory is not.

Reference Are Not Theory

Authors need to explicate which concepts and causal arguments are adopted from cited sources and how they are linked to the theory being developed or tested.

(p. 373)

Data Are Not Theory

Data describe which empirical patterns were observed and theory explains why empirical patterns were observed or are expected to be observed.

(p. 374)

Lists of Variables or Constructs Are Not Theory

A theory must also explain why variables or constructs come about or why they are connected.

(p. 375)

Diagrams Are Not Theory

While boxes and arrows can add order to a conception by explicitly delineating patterns and causal connections, they rarely explain why the proposed connections will be observed.

(p. 376)

Hypotheses (or Predictions) Are Not Theory

Hypotheses do not (and should not) contain logical arguments about why empirical relationships are expected to occur. Hypotheses are concise statements about what is expected to occur, not why it is expected to occur.

(p. 377)

Critical Things to Remember About Theory Building:

- A theoretical model is limited in no way except by the imagination of the theorist in what he may use as elements in building the model, or laws of interaction among the elements, or boundaries that he chooses to set on the model.

- A theoretical model is not simply a statement of hypothesis; nore is it a catalog of the units or variables employed and their definitions; nor is it a descriptive statement of a world of the scienfic imagination.

- The argument about the adequacy of the theoretical model is always and only an argument about the logic employed in constructing it.

- The argument about the reality of a theoretical model-that is, whether or not it indeed models the empirical world-is a scientific issue that is resolved by making research tests of the model.

- A theoretical model is a scientific model if, and only if, its creator is willing to subject it to an empirical test.

(Dubin, 1978, p. 12)